The travelling tiger

A tiger has undertaken an extraordinary 1,240-mile journey across India, which highlights why tiger ‘corridors’ are so important, explains Born Free’s Head of Conservation Dr Nikki Tagg.

A wild tiger (c) www.tigersintheforest.co.uk

Dr Nikki Tagg, Head of Conservation

Before Christmas, Times of India and India News reported the astonishing journey of a lone four or five year-old male tiger who walked from Maharashtra state in Central India to the eastern state of Odisha. The tiger zig-zagged his way across four states, in search of suitable territory, a food supply and a potential mate. Born Free has been working with a network of Indian conservation organisations to protect tigers in Central India for 20 years, and this recent news highlights the critical importance of tiger corridors to help ensure the long-term survival of this endangered species.

The young adventurer set out from the Tadoba landscape (in Maharashtra state) towards the end of 2021, or early 2022. Crossing water bodies, riverine habitats, mines, agricultural fields, roads, villages and towns throughout three states of Chhattisgarh, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh, he arrived in the east in Rayagada district, Odisha in June or July 2023. For a while, he apparently traversed between Odisha and the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh, before settling in Gajapati district in Odisha by September, a year and a half after setting off.

Reports from locals of a tiger in the region led Odisha’s forest and wildlife officials to find out what was going on. As he was not radio-collared, the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) set up camera traps and compared our wanderer’s unique stripe pattern with camera trap images from elsewhere in the country. He was quickly identified by WII as having been recorded during a camera-trap survey by the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), a member of the Born Free-supported Satpuda Landscape Tiger Partnership (SLTP), in Tadoba in 2021.

An image of ‘the travelling tiger’

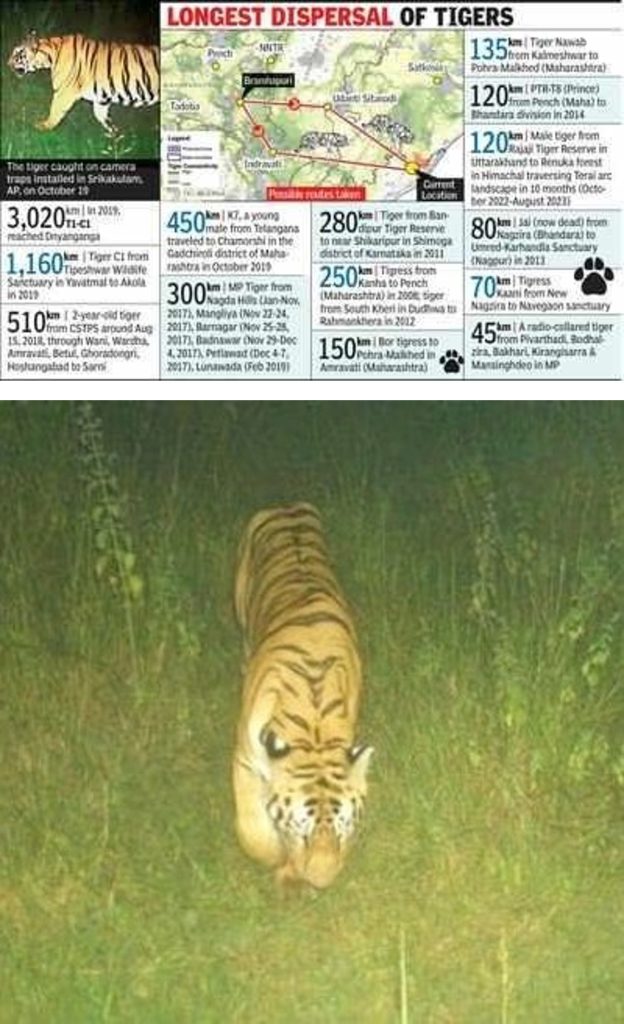

Odisha often receives dispersing tigers from the neighbouring state of Chhattisgarh, and numerous tigers have been recorded in India to have travelled tens or even hundreds of kilometres to find their new territory. However, this tiger’s epic 1,240-mile (2,000km) trek over an 18-month period is really quite rare and is one of the longest ever distances a tiger has been recorded travelling in India (second only to a radio-collared male who was logged to have walked over 1,860 miles (3,000km) in 2019!).

Most tigers, by the age of about 18 months, feel the urge to disperse, with an average dispersal distance of 17 miles (27km) for males and 3.5 miles (5.7km) for females. Tigers require vast areas of suitable habitat (the size of their territories ranges between eight square miles to 150 square miles [20km2 to 400km2]), free from intense human pressures, to access a sufficient prey base of large ungulates, including wild pigs and deer. Young tigers cannot remain in the same area as their parents as the resources available would not be sufficient to support their entire family. Dispersal is also important to ensure the genetic health of tiger populations. Tigers may go to extreme lengths in search of suitable habitat and resources, exemplified by this young male’s incredible journey.

The survival of tigers therefore depends not only on the protection of large unbroken tiger reserves but also on the connectivity between reserves via a network of corridors – non-protected forests and agricultural land through which wildlife can travel. The ability of tigers to naturally disperse hinges on the suitability and safety of these corridors.

Considering the route our intrepid tiger might have taken, Aditya Joshi, of WCT, explains that “there are two main routes that connect Maharashtra to Odisha that could be suitable for tiger dispersal”, emphasising how essential these corridors are to maintain connectivity to prevent cutting off dispersal routes and condemning populations of tigers to isolation and eventual extirpation.

All along this tiger’s monumental expedition, the tiger did not cause any conflict with people. However, since his arrival in September, he has started to kill cattle, as a way of sourcing the food he needs to survive. The young male is now moving 16-19 miles (25-30km) daily, feeding on cattle, and is being protected by Odisha officials. Those losing cattle are paid rapid compensation (within 36 hours) to prevent retaliation. A team of 35 forest staff has been deployed to alert people in bordering areas to be careful, and to keep their cattle tied up at night.

Although this young wanderer managed to make an exceptional journey across India, it is proving increasingly hard to protect corridors from development and to mitigate conflict between tigers and people along these corridor routes, meaning many other dispersing tigers will not be as successful. The construction of linear infrastructure such as roads, canals, train tracks, and power lines has the effect of breaking up the natural habitat, known as fragmentation, and creating a mortal hazard for tigers as they try to cross these new features in their landscape. Retaliation from aggrieved livestock keepers further threatens tigers as they attempt to disperse from one protected reserve to another.

Many organisations, including the partners of SLTP, are working hard to encourage the incorporation of mitigation measures, such as underpasses, that can help alleviate some of the problems created and maintain effective corridors. Of course, protecting the integrity of these vast landscape does not only benefit tigers. The forests they inhabit are essential as they play a crucial role in safeguarding biodiversity and sequestering carbon. Over 300 rivers and numerous streams originate from India’s six major tiger landscapes, providing water to millions of people downstream. Several million people across India depend on direct benefits and services from forests for their livelihood, including livestock grazing, fuel wood, forest products and building materials.

We wish our touring tiger success in setting up his new home and hope that conflict remains at tolerable levels for rural people. We also pledge continued efforts to help educate and empower, to reduce conflict, and to maintain connectivity across the Satpuda Landscape together with our SLTP partners so that many more tigers can travel freely and safely across India well into the future.