Remembering Bill

Today, we especially think of our Co-Founder Bill Travers MBE, who died 30 years ago this day. In a very special blog, our Executive President Will Travers OBE considers his father’s extraordinary, world-changing legacy.

Will Travers OBE

There are lots of things I knew about my Dad, who died on the 29th March 1994, aged 72.

I knew him to be an incredibly creative thinker – a problem-solver.

I knew him to be a great Dad and, briefly, grandfather.

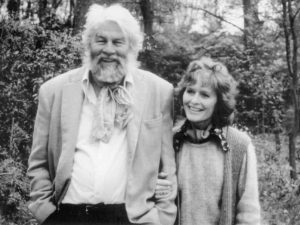

I knew that my mum, Virginia, was the love of his life.

I knew that he loved all his children deeply.

I knew him to be a man of endless compassion for animals and for people.

But there were some things I knew little of.

He almost never spoke of his time in the army, firstly as a Gurkha officer in 1939 on India’s deeply dangerous northwest frontier, and then as a Chindit, one of Orde Wingate’s men, parachuted many miles behind enemy lines into Burma and Malaysia to disrupt and harass and make as much trouble as possible, alongside the Chinese resistance.

His war diaries (such as they are) barely run to a dozen pages. As one of the very first people to arrive in Hiroshima after the bomb, his descriptions were harrowing and his remorse at the, in his words, unforgivable loss of civilian life, was unresolved.

His acting career had many highlights – working with such greats as Sidney Poitier and James Garner, Sophia Loren, Stewart Granger, Hayley Mills, Clint Eastwood and – for a few nights only, Dustin Hoffman on the stage in New York.

Bill and Virginia

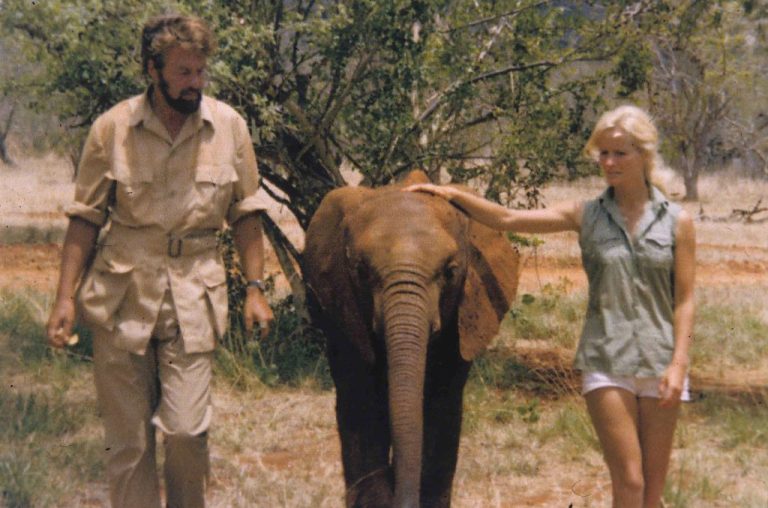

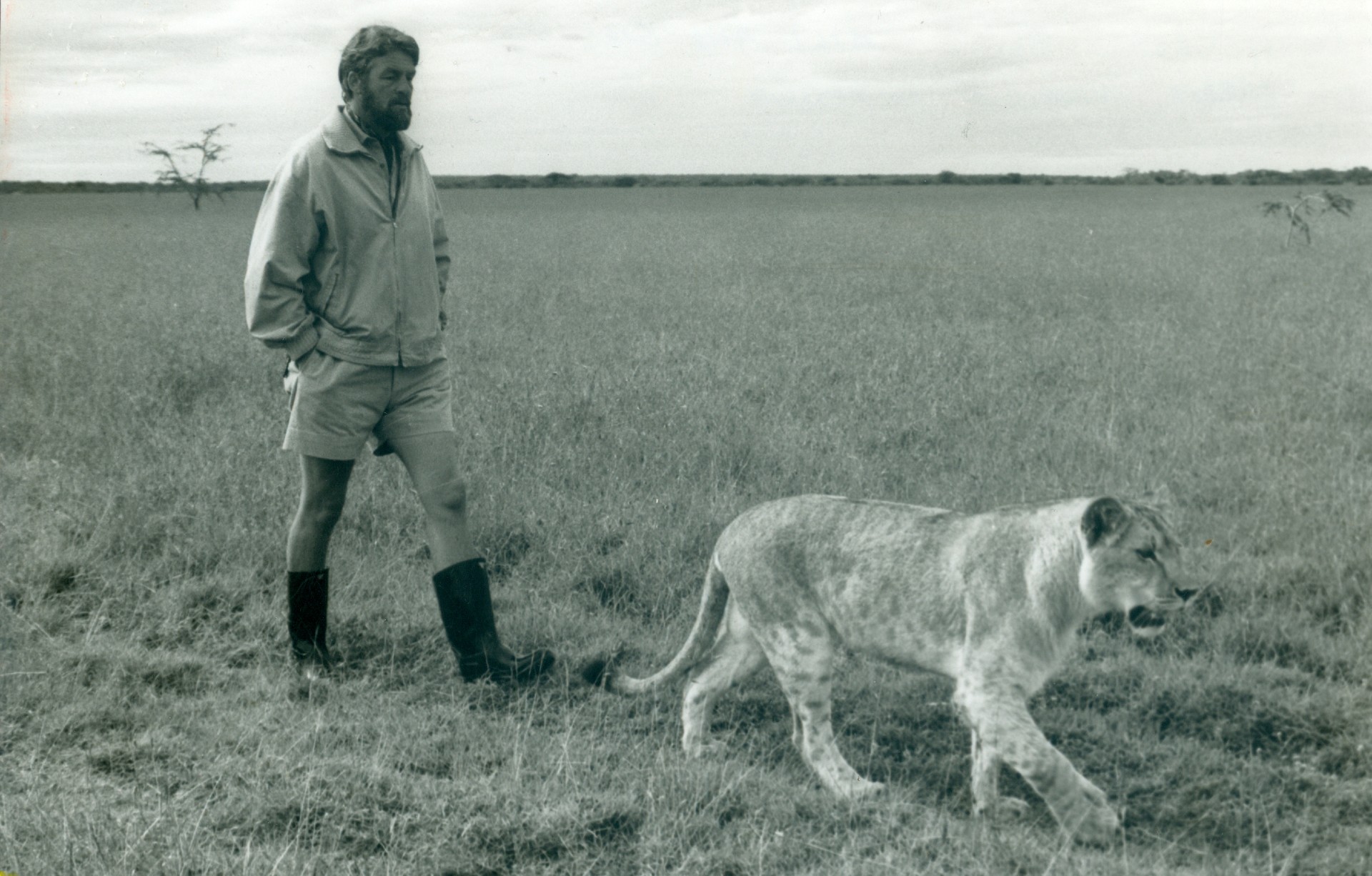

Born Free (1966) was a watershed film for him, travelling to Kenya with the family, playing opposite my mother Virginia for nearly 10 months, learning each day from George Adamson about lions – and life. It must have rubbed off on me too.

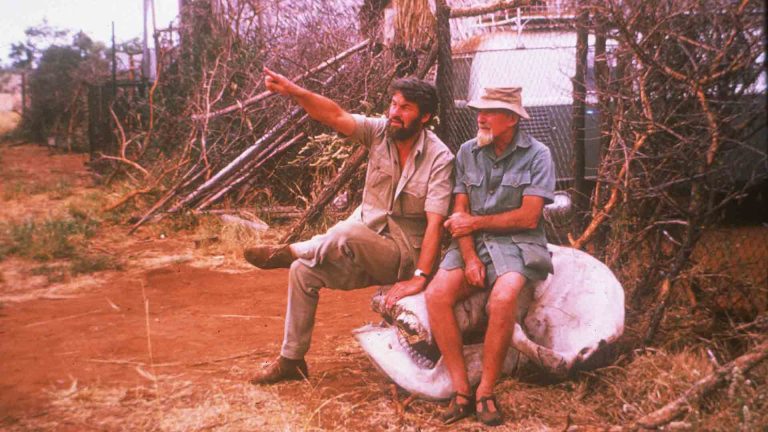

His subsequent documentaries (he almost stopped acting entirely) sought to break the mould, shattering the prevalent almost university-lecturer style delivery of natural history information, in an effort to gain access to living rooms around the world through The Lions are Free, which followed the story of three of the lions used in the film Born Free as they were returned to a wild and free life with the help of his great friend, George Adamson. Or Christian The Lion, with John Rendall, Ace Bourke and Christian, the lion from Harrods’ pet department who gained his freedom in Kenya’s Kora National Reserve, again thanks to George.

There followed a string of others: Simon Trevor’s Bloody Ivory (narrated by Judy Parfitt and Ian Holm), Oxford Scientific Films’ Deathtrap (presented by the extraordinary Vincent Price); The Sex Life of Flowers, saucily narrated by the great Freddy Jones; and, perhaps most moving of all, The Queen’s Garden (narrated by Virginia and featuring a short cameo by Her Majesty, the late Queen Elizabeth the Second), which followed natural history of the gardens at Buckingham Palace over a period of 12 months, and which I had the great good fortune to help him with, on occasion.

But it was his relentless determination to expose the cruelty, suffering and deprivation endured by with animals in zoos around the world that became his abiding passion – one could say, his obsession – for the last 10 years of his life.

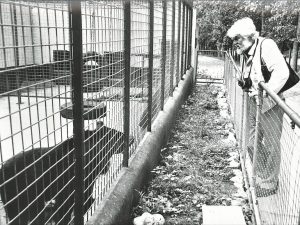

Bill Travers at Colchester Zoo in 1987

As our tiny charity, launched in 1984, took flight, he would pace the house, like a restless lion, trying to identify what it was, what could be said, what could be shown to people everywhere, to explain what he himself knew so clearly – that wild animals did not belong in zoos, should never perform to the crack of the circus trainer’s whip, should never leap through hoops of fire at the dolphinarium.

He could not see why the brutal, callous, or just plain indifferent exploitation of wild animals in captivity was so widely accepted, and almost every day for a decade we would discuss just that, putting some of his ideas into action and agreeing, sometimes, that unfortunately, the world wasn’t yet ready for his Born Free vision.

For the last two or more years of his life, he and a couple of colleagues spent much of their time voluntarily travelling round Europe, staying in small and often not very comfortable accommodation (where he contracted pneumonia), filming the mentally disturbed, deranged behaviour of wild animals in numerous zoos. The elephant brutally beating its head with his own trunk, the jaguar relentlessly passing, the giraffe systematically trying to lick the very paint off the bars of its enclosure. Their behaviours, analysed by the great animal psychologist Dr Roger Mugford, demonstrated a range of repetitive stereotypies, ‘displacement activities’ likely triggered by the futility and mental sterility of their dismal, impoverished lives. Dad called it ‘zoochosis’ and that expression has entered the lexicon.

The day he passed away, he had just returned from Liverpool, appearing on BBC2 with Virginia, speaking passionately about his most recent investigations. I called him early that evening, on my way back from London. He said he was tired. That was the last time I spoke to him.

His was a complex life. His late teenage and early twenties were consumed by war. His creative genius, for that is what it was, was well ahead of his time. His frustration with the slow pace of change was palpable. His outrage at the way we treat animals, and each other, burned.

But he was an extraordinary man. He still is.

REMEMBERING BILL