Killing of ‘super tuskers’ sparks scientific trophy hunting debate

Born Free’s Senior Wildlife Consultant Ian Redmond OBE, DSc(hc), FLS reports on the killing of much-loved ‘tusker’ elephants in Tanzania, and why recent news stories have sparked concern.

(c) georgelogan.co.uk

Trophy hunting is a hot topic at the moment. Two news stories in particular are fuelling a heated debate: one concerns the legal killing of ‘super-tuskers’ in northern Tanzania, earlier this year in January, and more recently in April – these are well-known elephants whose lives have been studied for decades by scientists in Amboseli National Park, Kenya, where trophy hunting is not allowed; three have been shot and their bodies burned after the trophies had been removed, and more permits have reportedly been issued despite a 30-year agreement between the two countries not to give hunting permits for this trans-boundary population. The second is that the UK parliament has recently passed the second reading of a bill to ban the import of hunting trophies of endangered species.

Ian Redmond OBE

Setting aside for the moment the ethical questions raised by selling the life of an intelligent sentient being with a brain nearly four times the size of ours, let’s look at the science. Conservation science is a complex multi-faceted discipline, but two main arguments emerge from pro-trophy hunting advocates; the first is numerical – that the number of animals killed is relatively small, they are claimed to be old and their loss is not significant to the species’ overall population; the second is that hunting areas allegedly bring an income from habitat that might otherwise be converted to agriculture or other land use that would be bad for biodiversity. Both may at first glance appear to be strong arguments, but do they stand up to scrutiny? And what of the many other considerations?

Some pro-trophy hunting commentators like to characterise opponents of the practice as being driven purely by emotions, ignoring the science they say supports trophy hunting, so I thought it might be useful to review the scientific rationale behind some very eminent scientists’ opposition to the ‘taking’ of ‘trophy’ animals from their habitat and social group. I’ll focus on elephants but recognise that these arguments apply to other species coveted by trophy hunters.

Ethology is a science – the study of animal behaviour. After decades of dedicated fieldwork, we now know that elephants live in a complex, multi-tiered, society with matriarchal family groups and bachelor groups maintaining long-distance communication. They also have cultural traditions and geographical knowledge that is passed down through the generations, not just from parent to offspring but also from grandparent to grandchild. This makes the term ‘post-reproductive old males’, sometimes used by hunters to suggest the impact of their killing is minimal in ‘conservation biology’ terms, entirely misguided. In fact, killing the elders of a community has many effects on the behaviour of the survivors and risks losing knowledge that may be critical to survival, for example during severe droughts that may only happen every few years. In the case of trophy hunting of predators such as lions, killing alpha males leads to social disruption, increased conflict and in some cases, infanticide, further depleting the population of the species concerned.

It is self-evident that low-level subsistence hunting of fecund species can be sustainable, but for slowly reproducing species with long lifespans and complex societies, even a low hunting pressure of 1-2 per cent per year can cause a long-term decline in addition to any genetic impact, as has been shown by computer modelling of ape populations.

Genetics is the study of a species’ genes and how inheritance of certain characteristics affects their evolution. Elephants have an unusual growth curve for mammals – instead of levelling off after puberty as in most species, including humans – male elephants continue to grow in overall body size as well as tusk size for their entire lives. Growth in female elephants levels off around 25 years (a decade after puberty) but even so, they seem to prefer to mate with the biggest, most impressive males, who are often those with the biggest tusks. This sexual selection for large males has led to the marked size difference between females or younger animals and males in their prime, in their 40s and 50s. Killing these successful breeders has, in only a couple of elephant lifetimes, changed the genetic make-up of most of Africa’s elephant clans, reversing millions of years of evolution!

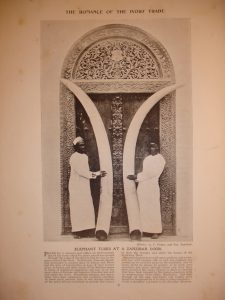

It is obvious that killing trophy animals in their prime effectively removes their genes from the gene pool, and so selects against the very characteristics valued by the hunters. This is un-natural selection, and results in the removal (or at least a reduction) of genes for big horns/tusks/antlers/manes over time. Even the term ‘super-tusker’ elephants – now defined as an elephant with at least one tusk weighing more than 100 pounds – is indicative of that change. Look at the size of trophies in the 19th century, such as this pair photographed in Zanzibar and thought to have originated on Mt Kilimanjaro – imagine the size of elephant able to wield them! Now HE was a super-tusker!

Trophy animals are also likely to be the fittest, in evolutionary terms, and the genes for large secondary sexual characteristics may be linked to those for a strong immune system and the ability to survive emerging diseases. The fact that they have lived to reach their prime implies their immune system is effective!

At least one of the three Amboseli tuskers killed recently had barely reached his prime – from a photograph of the carcass, scientists in Amboseli who have detailed records of hundreds of their study animals, identified him as Gilgil, the 35 year-old son of a magnificent tusker known as M22 Dionysus. We will never know whether Gilgil might have exceeded his father’s tusk size – his genetic line ended in September 2023 when he was shot. M22 Dionysus did have other offspring (Cynthia Moss, pers.comm.) but if the agreement not to allow trophy hunting of this trans-boundary population is not reinstated, any of them growing tusks in excess of 100 pounds weight will likely end up on some hunter’s wall rather than maturing into successful breeding males.

Given the competition among hunters to bag the biggest trophies, it is ironic that elephants put on more ivory per year in later life than when young, so the best way to get the biggest tusks is to let them die of old age!

The economic arguments for and against trophy hunting rather depend on the nature of the alternatives being proposed. While it is true that some rural communities in Southern Africa may benefit from part time jobs as trackers or porters for trophy outfitters, and the meat of carcasses, research has shown that only a tiny percentage of the cost of a hunt typically goes to local communities, which begs the question: are there not better ways to lift these communities out of poverty and still protect biodiversity?

In public debates, I use the example of mountain gorillas, which a century ago were the ultimate trophy animal, only accessible to the richest hunters. Today, living gorillas are the basis for a multi-million-dollar tourism industry bringing significant foreign exchange for impoverished governments, huge employment opportunities and tangible community benefits from revenue sharing. What was it that changed 45 years ago when gorilla tourism began? The answer is habituation – winning the gorillas’ trust – and then the sharing of life-affirming experiences of peaceful gorilla encounters in documentaries, articles, movies and social media.

The proliferation of amazing mountain gorilla photos and videos is a measure of this change in public attitudes; the steady recovery of mountain gorilla numbers is a conservation success story that would not be possible if these families of gorillas still feared humans as harbingers of death.

Likewise with elephants; a recent analysis of elephant population estimates across much of Southern Africa reveals that between 2018 and 2022, areas with trophy hunting saw a fall in elephant numbers. This is not to say that statistically significant numbers of elephants were killed; rather it suggests that elephants leave areas they perceive as dangerous when they are able to do so. Their flight distance also increases, which makes photo-tourism more difficult – and dangerous, because frightened elephants are more likely to react aggressively when encountering people. This puts locals as well as tourists at greater risk.

Tool or trophy? An Amboseli tusker rests his trunk. Elephant tusks are modified incisor teeth that grow throughout the life of those elephants who have them and are used with the trunk to harvest food plants (eg bark, vines and roots), dig for minerals and as weapons for defence against predators, in play-fighting and display. (c) Ian Redmond

Not all tourism focuses on photography, however. Animals previously targeted by trophy hunters could become the focus for adventure or cultural tourism – where the experience of tracking and observing them on foot is what clients pay for – similar in some ways to hunting tourism, but without killing the target. This can be developed without the infrastructure and facilities that mass tourism requires – in fact, it is the lack of amenities that makes it more attractive to those seeking a wilderness experience, with the knowledge of indigenous people and local communities to enrich the experience. What an opportunity for African entrepreneurs!

What about the impact on the ecosystem of killing an elephant like Gilgil at just 35 years old? Ecology is the study of the intricate relationships between species of animals and plants. In the case of mega-herbivores, their role in the ecology of their habitat is crucial for nutrient recycling, seed dispersal and soil health – they are the #GardenersoftheForest and Savannah. The fact that across Africa, elephant numbers have plummeted by ninety per cent or more in the last century means that every individual alive today is critical – each one performs an important service.

Killing an elephant decades before death from old age, for example, means that roughly 52 tons of manure and millions of seeds are not being spread every year. Elephants can live into their 60s, so we can calculate that if Gilgil had lived to 65, he would have dispersed another 30×52 = 1,560 tonnes of first class organic manure containing billions of seeds and feeding trillions of invertebrates – a loss to the ecosystem that is now recognised to have economic as well as ecological consequences, and therefore a huge loss to us all.

Payment for ecosystem services (PES) attributable to keystone species is a new concept being pioneered by www.rebalance.earth. The idea is that the monitoring of ‘client animals’ by rangers, community members and even tourists could build a culture of conservation and an economy that values nature. Today’s reliance on wildlife tourism revenues (or even trophy hunting fees) to finance conservation and alleviate poverty has a fatal flaw: if a war or a terrorist atrocity or a pandemic stops tourism, the finance for conservation dries up. PES, however, would continue to bring economic benefits as long as the communities are collecting the data to prove the ‘client animals’ are alive and well in their ecosystem.

The potential value of PES is staggering, even though most ecosystem services do not yet have a market value. Only carbon sequestration and storage currently has a tradable value and despite the well-publicised examples of fraudulent carbon credits, the voluntary carbon market has already financed the conservation of numerous important biodiversity-rich habitats and benefited neighbouring communities. Thus far the role of animals, however, has largely been ignored. In 2019, however, it was calculated that each African forest elephant is responsible for an additional £1.4 million ($1.75 million) worth of carbon being stored in ‘above-ground biomass’ (mostly wood) in the Congo Basin (and the market price of carbon goes up every year). Similar calculations have yet to be published for savannah elephants but research shows they significantly increase the level of soil carbon and other nutrients.

In summary, the unintended consequences of trophy hunting include:

- Social disruption leading to increased mortality through fighting and, in some species, infanticide;

- Increased flight distance and aggressive behaviour towards humans;

- Loss of cultural knowledge and behaviour that may be critical to survival;

- Killing the ‘best’ specimen is the opposite of natural selection, with long term evolutionary consequences if it happens over a long period.

- Ecological impact – removing an individual in his/her prime removes decades worth of the ecological role of that individual.

- Loss of natural capital and potential payment for ecosystem services.

Moreover, as soon as hunting becomes commercial, the economic imperative to make more money has time and again proved that many hunters and fishermen have little self-restraint, and that legally imposed restraints only work if accompanied by strong enforcement. Thus, whether you think trophy hunting is a legitimate way of contributing to habitat conservation or an unethical, atavistic perversion left over from the colonial era, there are far more scientific arguments against than in favour!

Take Action

Add your voice to the petition urging the President of Tanzania to restore the agreement not to allow trophy hunting of this trans-boundary elephant population.