In conversation: Anish Andheria, President of the Wildlife Conservation Trust

28 August 2023

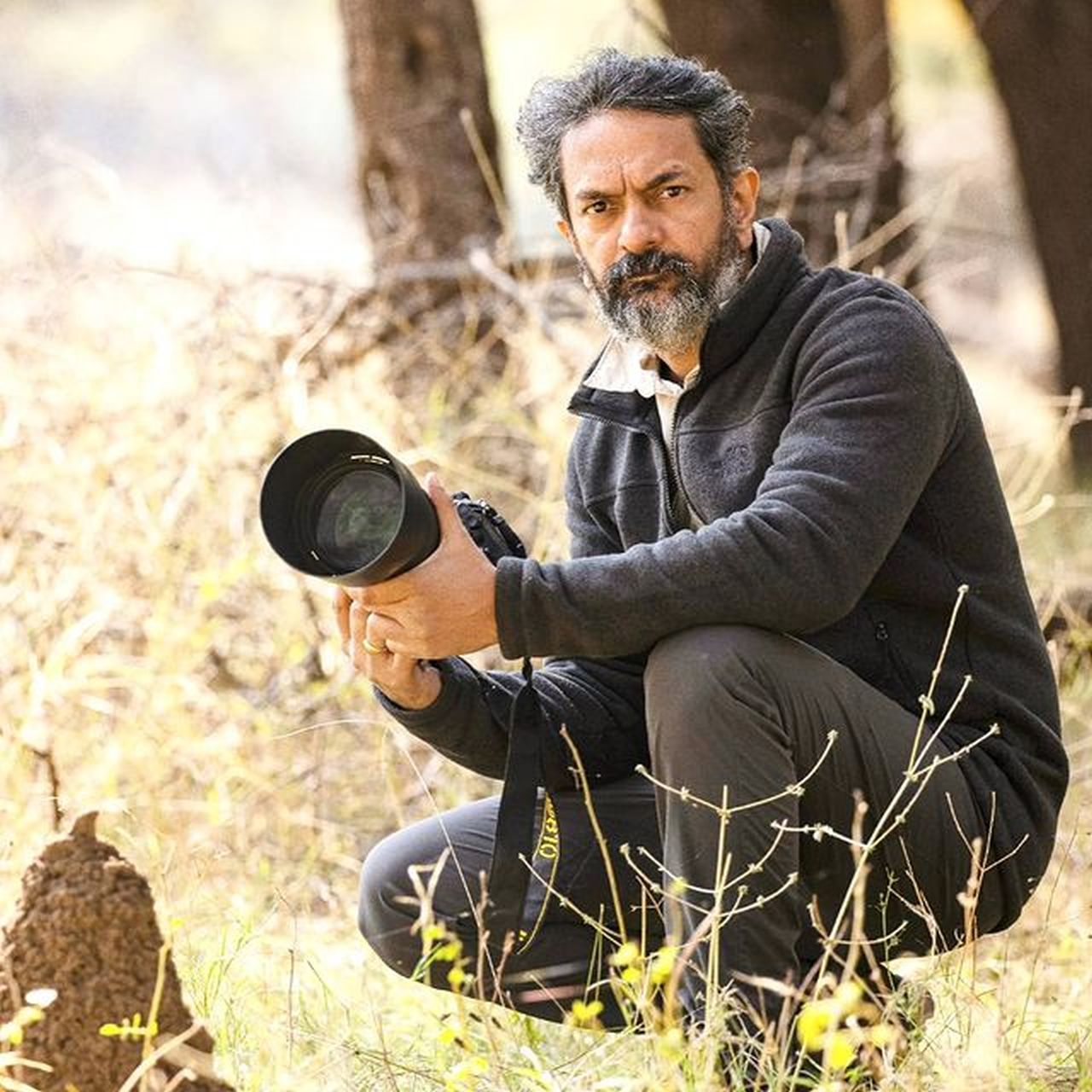

IN CONVERSATION: ANISH ANDHERIA, PRESIDENT OF THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION TRUST

Earlier this month, we spoke with Anish Andheria, President of the Wildlife Conservation Trust, one of the partners of the Satpuda Landscape Tiger Partnership.

(c) Yashvardhan Dalmia

Since 2004, Born Free has helped coordinate a network of nine conservation organisations in India, working with local communities to support tiger conservation. As one of the Satpuda Landscape Tiger Partnership (SLTP) partners, the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) aims to safeguard India’s ecosystems via a holistic programme that equally emphasises wildlife conservation and community development. In doing so, WCT aims to safeguard key wilderness areas to benefit both people and wildlife. We spoke with Dr Anish Andheria, President of WCT.

How did you become a tiger conservationist?

My education was in fluid mechanics and surface chemistry, but I was always very interested in wildlife since my childhood. I started rescuing snakes and other animals like crocodiles and birds when I was in Grade 8. Unfortunately, as there were no good Master’s programmes in wildlife conservation, I ended up studying engineering.

However, my interest in nature continued and I started publishing a lot of my work and did a lot of photography wherever I travelled. During my Master’s and PhD, I used to take sabbaticals and do a lot of tiger research work with Ulhas Karanth from the Wildlife Conservation Society. After my Ph.D., I joined Sanctuary Asia and worked there for nine years. And then, in 2009, I joined Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT). I was the first employee there and helped build the team. Now, we are a team of around 90.

Why are tigers important?

Well, like any large carnivore, tigers sit at the top of the food chain, so they keep a check on the herbivore densities and in a way regulate the entire ecosystem. They are therefore an indicator of the health of the ecosystem -– to measure what is happening in the ecosystem, instead of going and working with plants or looking at how many grass blades there are in the forest, it’s easier to study tigers. And if the tiger population does well, you know that everything else is likely also thriving. Therefore, tigers become a barometer, similar to top carnivores in other ecosystems. If you are in the Arctic, then you look at the polar bear. If you’re in the Amazon, then you look at jaguars and so on and so forth.

What are the main threats to tigers?

The biggest threat for tigers globally is the illegal trade in tiger body parts. Sadly, there is a huge international demand for every single body part of the tiger. This puts pressure on the population across the planet. In India, tigers are doing fairly well, but globally not so much. India, home to the Bengal tiger, has more than 70% of remaining tigers, yet there are several threats to India’s population as well. The most significant threat in India is forest degradation and fragmentation, as tigers require vast contiguous stretches of habitat. Furthermore, in India, there is direct poaching of tigers for international trade and poaching of prey for consumption within the country.

We also must make sure that local people’s interaction or their connection with the forest stays intact because without their support, we will not be able to protect the forest or tigers. Protection is one thing, but I would give the culture, the resolve, and the tolerance of the communities the majority of the credit when it comes to conservation successes.

In the absence of prey, tigers may attack livestock which may lead to conflict with people, resulting in tiger deaths. There are also unintentional tiger deaths because of roads and electrocution – electrocution is an emerging threat to tigers. Electric fences are built by farmers to control the herbivore population and keep them out of their farms, but tigers and leopards fall prey to it. Climate change is also a big threat because a lot of the habitat is now changing and degrading.

What actions does WCT take?

WCT uses the tiger as a guiding light. We work on several species in other habitats, but the tiger is why the organisation was set up, and the tiger it has guided us to get involved with landscape-scale problem-solving projects. We work a lot on conflict mitigation between people and large carnivores, especially tigers. We also estimate tiger densities not only inside, but outside protected areas in wildlife corridors. We cover between 800,000 hectares (8,000km2) to one million hectares (10,000 km2) of corridor area every year and that gives us a lot of information on the challenges that wildlife faces in non-protected areas and challenges that people face because of carnivores.

This allows us to weave in solutions that are far more holistic. We are also working with communities to reduce their dependence on the forest since if communities keep going to the forest, there is going to be conflict. We run an energy-efficient water heater project called the ‘Heater of Hope’ where we are trying to provide alternatives to fuel wood and that has really changed the way people use the forest. We try to understand the socio-economic and socio-cultural structures to see how behavioural change can be brought about in communities. Impoverished communities often rely on natural ecosystems for survival, thus they will not benefit if the forests go, but they are forced to destroy the forest because they have no other alternative. So that’s the area of interest and we try to approach it from many angles – science, social science, conservation biology, legal frameworks, and so on.

Tell us about a typical day for you as a tiger conservationist?

My days are almost 15 to 16 hours long, not because I am forced to work that long but because I love what I do. I love to keep thinking about solutions, partnerships, strategizing programs, and working closely with my teams to develop strategies to solve conservation issues. And I am blessed to have a great team. Most of the hard field work is done by them. My role is to try and weave all of those together, and also take it to the next level – to the policy makers.

We work with the state and central governments and try and translate our research work into action. We are on several state boards of wildlife and also I am a member of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA). All of our work is designed in such a way that it can eventually be translated into larger change. I also look at reports, read other people’s work, and coordinate with a lot of people within India and internationally, with the forest department, other NGOs, other researchers, and so on.

Any major successes?

Our tiger population estimation programme is the longest programme we have had. It’s been running eleven years now and we have been doing it largely in the states of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. This has translated into several successes in securing large landscapes and several parks for wildlife. There were people on the ground who always knew that these areas are important, but once we started conducting systematic studies, it added a lot of weight to what those people were saying. WCT played a catalytic role in getting several new parks declared, getting the buffer zones expanded, getting the core expanded, and getting the corridors notified.

Secondly, the energy efficient water heaters are great contraptions and now there is a huge demand for them in areas which have traditionally seen the highest interaction between people and tigers. These water heaters have reduced the usage of wood and carbon dioxide emissions significantly, reducing people’s reliance on natural forest resources and improving standards of living.

Future plans for WCT?

We have very ambitious plans. Our aim is to secure 30% of India for nature. We currently have 5.25% under the protected area network. A lot of other areas of habitat are in reasonably good shape, but they are not really well protected. We want to see how that can be done, and that obviously will need a lot of partnerships like the ones we are doing at the national level with other NGOs (non -governmental organisations) and the government.

We work with a lot of other endangered wild animals like gharials, Ganges river dolphins, pangolins, and Eurasian otters. We want to expand our policy-related work so that it has an even wider impact. We also want to see how we can bring about transformation with quality data. We could partner with other organisations who have data and then try and integrate programs. We are thinking of partnering with the social organizations, and working to see how climate change can be tackled through several programs from the livelihoods and efficient agriculture perspective. The climate is changing rapidly. The monsoon is shifting. So, we feel that if we can move towards agroforestry, then there is a win-win on both sides.

Would you encourage the public to be hopeful?

India is doing a lot of things right for tigers. However, there are 18 tiger states, but tigers are only doing well in about six or seven of them. There are lots of success stories from these states that are doing well that other states can learn from. There should be more exchange programs. The better performing states should be incentivized, encouraging greater investment in tiger conservation. If that happens, then automatically other states will get inspired.

Had a memorable encounter with a tiger?

I have walked several thousand kilometres in tiger habitats in my lifetime and had several encounters with tigers. One of those sightings was in Bandipur Tiger Reserve during my Master’s while I was collecting data. We were walking down a slope and the road was cutting through a stream. The noise from the stream would have muffled our footsteps and we saw a male tiger sitting in the stream barely 20 meters from where we were. It was facing the other side.

We saw the tiger before it saw us, and then obviously by default the tiger turned and looked at us – we froze, not knowing what to do because it was very close. Thankfully, it just crouched, then stood up and walked back into the forest. Immediately, from where the tiger had entered few spotted deer and a four-horned antelope ran out and almost crashed into us, as they too hadn’t realised that there was a tiger sitting only a few metres from them. It was quite the experience and it speaks volumes about how timid large carnivores really are. They are not the bloodthirsty beasts they are often thought of!

Why are people important in conservation?

When we work on tiger conservation, we really don’t interact with tigers. Tigers don’t understand our language. We claim that we know what they need, but if we had known, then human beings would have done better for them from the beginning. Since our knowledge is also fuzzy, the best way we can influence wildlife is by working with communities.

I have a huge respect for people living in and around the forest, especially in India because they really pay the costs of living alongside tigers and yet they don’t go about killing wildlife. It is very important that their inherent love for nature stays intact for generations to come. We also must make sure that their interaction or their connection with the forest stays intact because without people’s support, we will not be able to protect the forest or tigers. Protection is one thing, but I would give the culture, the resolve, and the tolerance of the communities the majority of the credit when it comes to conservation successes.

Any advice for budding conservationists?

Conservation is very complex. The more you work on it, the tougher it gets because you realise that there is no easy and permanent solution. So, you have to be adaptive and you need to stay humble. You cannot dislike human beings and say: I love wildlife but I hate human beings. You have to think about people. Unless you can create programs that are good for people, you will not be able to save wildlife. You cannot justify saving wild animals if people are going to die either out of starvation or if they fall prey to wildlife. So budding conservationists will have to have a balanced mindset, and be ready to learn and be flexible.

How can we help tigers?

I think the people living in and around the forest are doing a lot for the forest because they are hardly using electricity, they recycle pretty much everything they use, and they grow what they eat, so it’s all local. We have to learn from them and lead a lifestyle where we can buy things that are local. And obviously, conserve electricity and water. All these things are clichéd, but they are important.

Individuals can either contribute financially or volunteer with organiszations. Whatever background, you have skills that can contribute to conservation. No matter where you are, whether you’re a writer or painter or whatever profession you are in, if you love wildlife, you will be able to contribute to conservation. Use less, reuse much more, walk a lot, and live a healthy lifestyle. And I think healthier people find healthy solutions.

How is Born Free to work with?

The Satpuda Landscape Tiger Partnership is acting as a glue to bring together a number of NGOs that are doing good work that, if not for Born Free, would have worked in isolation of each other. NGOs are generally busy with other tasks and hardly have any time to enter partnerships. I believe the biggest benefit of Born Free has been in this partnership where people working in the same landscape have come under a common roof and are interacting more than they were doing before.

Anything you’d like to say to Born Free supporters?

I am humbled that Born Free supporters, who may not know much about the individuals organiszations in the SLTP network, are nonetheless supporting Born Free so that the SLTP partners can continue protecting tigers here in India. Their financial support will go a long way.

You can help!

You can support tiger conservation by donating or by adopting our tiger Gopal – rescued from conflict and given loving care for life in a Bannerghatta sanctuary.

Want to know more? Watch Anish Andheria discuss a number of conservation topics by clicking on the buttons below.

TYPICAL DAY AS A TIGER CONSERVATIONIST MEMORABLE TIGER ENCOUNTER PEOPLE & COMMUNITIES SUCCESS OF WCT